Arizona Immigration Law, Part I: More severe control over illegal foreign residents in Japan; “No More Attempts, No More Entry, and No More Stay”

Vincent A. @ ELC Research International

I originally wrote this article eight years ago, i.e., in 2010. So, the story could be partially out of date, but still the gist thereof would be true, I believe.

Background of the Arizona Immigration Law

The U.S. Federal District Court has issued an injunction against the Arizona immigration law, enacted in April 2010, which is designed to banish illegal immigrants. Although the enforcement of the entire law is currently postponed, the injunction has been given upon only a few sections of the immigration law such as one which requires police officers to inquire about the immigration status of suspicious persons. The Arizona state government has stated that they will appeal the injunction and will nevertheless enforce sections of the immigration law not blocked by the court ruling.

There are an estimated 11-12 million illegal immigrants in the U.S. and a half of them are concentrated in U.S.-Mexico border states such as California, Texas, and Arizona. Arizona has a total population of 6.6 million, with 30% (2 million) being Hispanic with origins in Central/South America. Among the Hispanics, 450-500 thousand people are considered to have migrated illegally, and Arizona is known as the state having the highest ratio of illegal immigrants compared to the total state population. The Arizona immigration law has been criticized harshly as being discriminatory to Hispanics or as infringing upon their human rights, particularly with respect to one section which obliges the police to inquire about someone’s immigration status if illegal immigration is reasonably suspected. However, considering the growing number of illegal immigrants, nearing 10% of the total population, it is not unreasonable from the standpoint of social policy theory that the Arizona state government attempts to impose tougher immigration law enforcement. However, this law, and discussion of it, is not as simple a matter as it might seem. In fact, quite a number of Americans seemingly favor this controversial law (*1), and Oklahoma, Utah and South Carolina have stated they plan to follow Arizona’s lead on tougher immigration control.

Japan to tighten the immigration control, declaring “No More Attempts, No More Entry, and No More Stay”

For Japanese immigrants like us or Japanese students living in Canada, there is another factor that makes us to hesitate to criticize the Arizona immigration law: the immigration control in Japan rivals or even surpasses Arizona’s, and the control has been becoming even tighter over the years.

Japan has two legal systems for foreigners: the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act which controls all foreign nationals entering into or departing from Japan, and the Alien Registration Act which controls foreign nationals staying in Japan for longer than 90 days (*2). Japanese immigration control is known for its stringent procedures: for example, no one is allowed to leave Japan without the permission of an immigration officer. Nonetheless, the number of illegally resident foreign nationals soared in the 1990s. Due to the upsurge of illegal employment and a rash of crimes conducted by foreign nationals, particularly organized crime engaged in by foreign criminal organizations, public safety in Japan was worsened, causing escalated social unrest. Worrying about this, the Immigration Bureau of the Ministry of Justice, the government of the City of Tokyo, where many illegal immigrants are concentrated, and the Tokyo Metropolitan Police are cooperating closely, with the aim of putting into place a strict crackdown on illegal immigrants and illegal employment while taking tougher measures to foreign nationals landing in Japan.

How committed they are to these control measures is shown by the Immigration Bureau’s campaign slogan: No More Attempts, No More Entry, and No More Stay. Let’s look at each part of the slogan. “No More Entry” refers to implementing stricter examinations for those entering the country and blocking foreign nationals who do not meet the residential eligibility requirements. It includes not only more rigorous examinations upon the landing but also enhanced technology against forged and falsified documents, effective use of the “Residential Eligibility Certificate System” (*3) and biometric immigration screening for personal recognition. “No More Stay” means measures to reduce illegal foreign residents by intensifying the crackdown on illegal immigrants and workers already in Japan, strengthening the criminal penalties for illegal foreign residents and implementing the Departure Order System (to be discussed later). Lastly “No More Attempts” means a preventative measure which aims at discouraging foreign nationals from entering Japan for the purpose of staying illegally, by making it known internationally that Japan has new tough immigration examination procedures and severe criminal punishments against illegal residence.

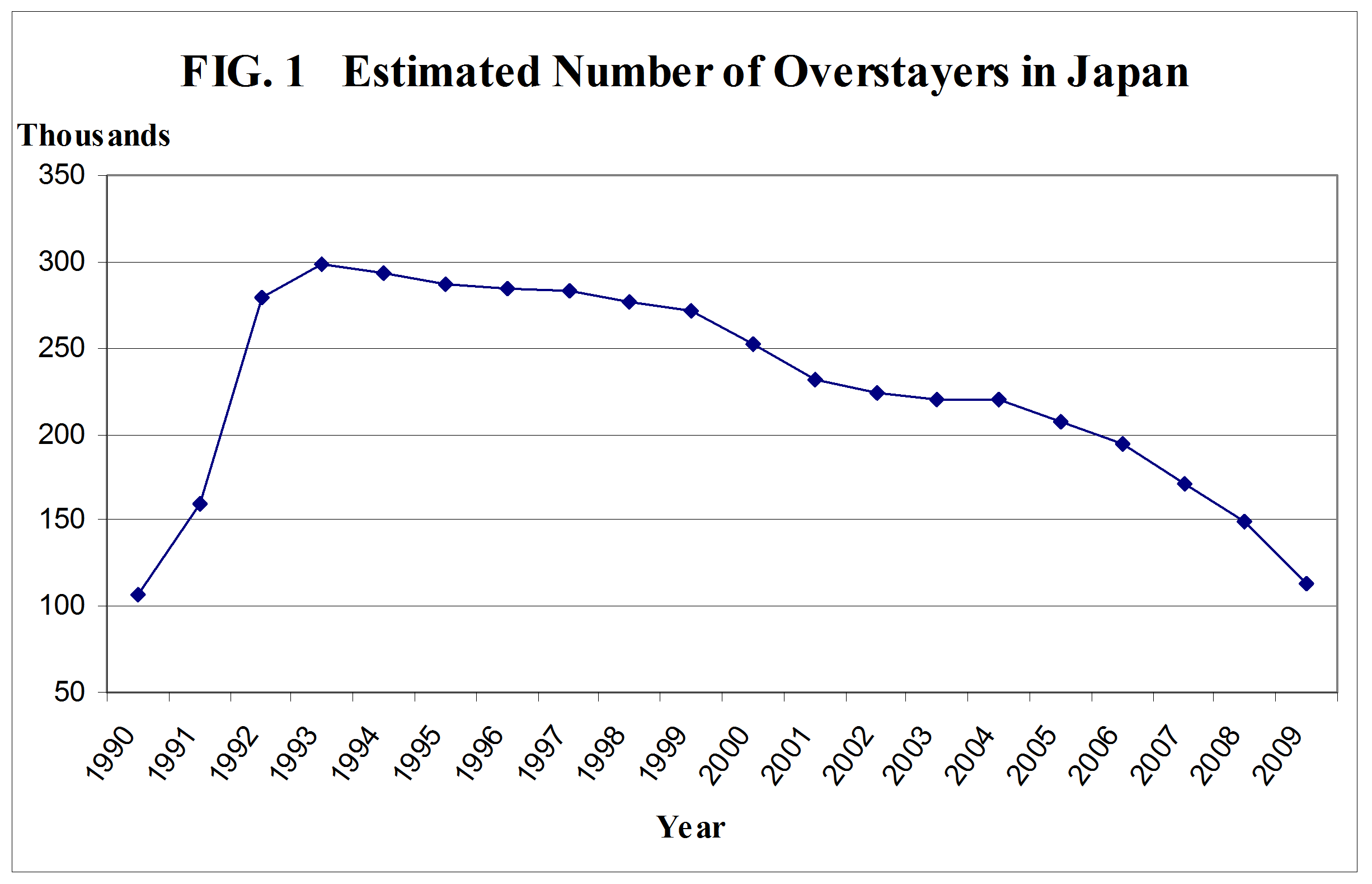

FIG. 1 is evidence of how successful, under the above mentioned campaign slogan, Japan’s tightened immigration control has been. In Japan, illegal residence is classified into two categories: “illegal stay” and “overstay.” If a person enters Japan illegally and stays without permission, it is categorized as “illegal stay.” If a person enters legally but remains in Japan after the allowed duration has expired, it is called “overstay.” FIG. 1 concerns the latter, and shows the changes in the number of overstayers from 1990 to 2009, the estimation being somewhat easier for the latter than for the former (*4). The reader will note first in the chart that the number of overstayers significantly increased in the early 1990s, started decreasing in the mid 1990s, continued its downward trend faster in the late 2000s, finally returning to the 1990 level in 2009. Let’s discuss further the major factors in this success.

The number of overstayers peaked at 300,000 in 1993 after having increased rapidly since 1990. After 1995 the illegal overstays decreased in number when a major crackdown was conducted by police. But it still remained high at around 270, 000.

To reinforce the crackdown, major revisions were made to the Immigration Control Act in the year 2000. The landing denial period for banning the re-entry was extended from one to five years, which means deported foreign nationals could not re-enter Japan for a five-year period from the day of their deportation under the revised Immigration Control Act. New criminal offences termed “unlawful stay” and “unlawful overstay” were also added, which clearly indentifies illegal residence as a criminal matter (Article 70-2 and 5). Any person who commits these offences can be punished with imprisonment, with or without labour, for up to three years or could be levied a fine of up to 300,000 yen (approx. U.S. $3,000), which was later revised to “up to 3,000,000 yen” (approx. U.S. $30,000).

Before the amendment, illegal residence was a violation of the Immigration Control Act and was subject to the imposition of deportation, but was not regarded as a criminal offence. It is particularly significant to note that the revised Immigration Control Act specifies illegal residence as a criminal offence because, similarly to the Arizona immigration law, the Japanese Immigration Control Act hereafter authorizes police to question anyone they reasonably suspect of being an undocumented immigrant or an individual attempting illegal activities. (Further details will be in Part II in the next issue.)

The revision of the Immigration Control Act in the year 2000 had a noticeable impact. Just before the day when the revision came into effect, a large number of illegal immigrants appeared at the Immigration Bureau voluntarily to receive the existing penalty (deportation from Japan with no criminal charge and the landing denial period of 1 year). The revision evidently triggered the large reduction of illegal residents after the year 2000 in FIG.1.

In 2004 the landing denial period for banning the re-entry of those who had been deported in the past and who were deported again, was extended from 5 years to 10 years, and the Departure Order System was newly established as previously mentioned. Under this system, foreign nationals who illegally overstay and who meet certain requirements such as voluntarily presenting themselves to the authority are ordered by the authority to depart voluntarily. This is to encourage voluntary departure of overstayers. The authority does not put them in detention as with the deportation procedure. The landing denial period is reduced to one year for those who voluntarily leave Japan under the departure order. So, what Japan had done since the 1990s is exert greater control through a dual-lobed strategy: defining unlawful stay as a criminal offence and putting more severe crackdown on illegal foreign residents on one hand, and encouraging voluntary departure of overstayers on the other hand, both aiming at “No More Stay” of illegal foreign nationals.

Furthermore, in 2007 a new screening measure was introduced which requires the submission of personal identification information including fingerprints and a facial photograph taken at the landing. If a foreign national refuses to submit this information, that person will not be permitted to enter Japan, and will be required to leave the country.

As a result of these stricter measures the number of illegal overstayers has fallen to 1/3 of its peak number in 1993. The Japan Immigration Bureau has stated that they will continue efforts aimed at reducing illegal foreign residents plus continue strengthening the measures to detect false marriages and fake international students who are staying illegally for purposes other than those claimed.

In the case of Arizona’s new immigration law, the authorization for police officers to question an individual about whom they are reasonably suspicious has been criticized. However, in Japan, the right to question the residential status or period of stay is not limited to police officers. It is legally extended to immigration control officers and immigration inspectors as well as marine safety officers, drug enforcement officers and Public Security Agency officers, all of whom have the right to investigate and arrest. Furthermore, even personnel who work in the alien registration section of any national or local public organizations and those who work in employment bureaus are similarly authorized. This first segment of our discussion of immigration has presented some background information relating to the Japanese and Arizona immigration laws, which will be discussed in greater depth in the next issue (Part II). Also, in Part II, upcoming even tighter control in Japan — replacing the Alien Registration Act by a new Alien Residence Control System coming into effect in 2012 — will be discussed. In Part III, issues relating to the Arizona immigration law will be discussed in comparison with the immigration control system in Japan.

[Translation: Atsuko Umeki, Proofreading: David Gordon-MacDonald]

*1: “Arizona Immigration law divides Californians” CNN Politics, May 31, 2010

“CNN poll: Most back Arizona law but cite concerns about effects”, CNN Politics, July 28, 2010

http://www.cnn.com/2010/POLITICS/07/27/poll.immigration.discrimination/?iref=obnetwork*2: One part of the Immigration Control Act, which includes the entry and departure procedures, is also applied to Japanese who enter or leave Japan; however, the rest of the law all relates to foreign nationals such as the residential eligibility. Both the Immigration Control Act and the Alien Registration Act show a strong intention of “controlling” foreigners in Japan.

*3: The Residential Eligibility Certificate System allows a foreign individual or his/her agent to submit while in Japan an application for the Residential Eligibility Certificate before applying for a visa. The certificate proves that the applicant fulfills various conditions prescribed by the Immigration Control Act and is eligible to acquire a certain residential status, while an application for a visa is to be submitted only through a regional immigration authority outside of Japan. The Residential Eligibility Certificate System has an advantage of shortening the time required to obtain a visa and complete the immigration procedure. It also provides the immigration officer a clearer indication of an individual’s eligibility when he or she lands in Japan, which, in the end, leads to improvement of immigration inspection procedure. The government of Japan has encouraged foreigners to use this system when acquiring a visa.

*4: The graph of FIG. 1 has been prepared by the author based on the data from “Immigration Control 2002” and “Immigration Control 2008”, the white pages issued by the Immigration Bureau of the Japan Ministry of Justice. It is estimated that the number of illegally landed residents was 30 thousand at the peak and was projected to come down to 15 to 20 thousand in 2009.

“Immigration Control 2008” (Japanese version)

http://www.moj.go.jp/nyuukokukanri/kouhou/nyukan_nyukan90.html

“Immigration Control 2008” (English version)

http://www.moj.go.jp/nyuukokukanri/kouhou/nyukan_nyukan91.html

This article is a revised version of the article entitled “Arizona Immigration Law: What’s the Problem? [Part I] More severe control over illegal foreign residents in Japan; “No More Attempts, No More Entry, and No More Stay” printed in Japonism Victoria, vol. 5 no.6, 2010 published by Japanese Canadian Community Organization of Victoria.

You can download the PDF version of this article from the following link:

https://www.japonism.media/library/sod100901.pdf

> Arizona Immigration Law, Part II

> Arizona Immigration Law, Part III